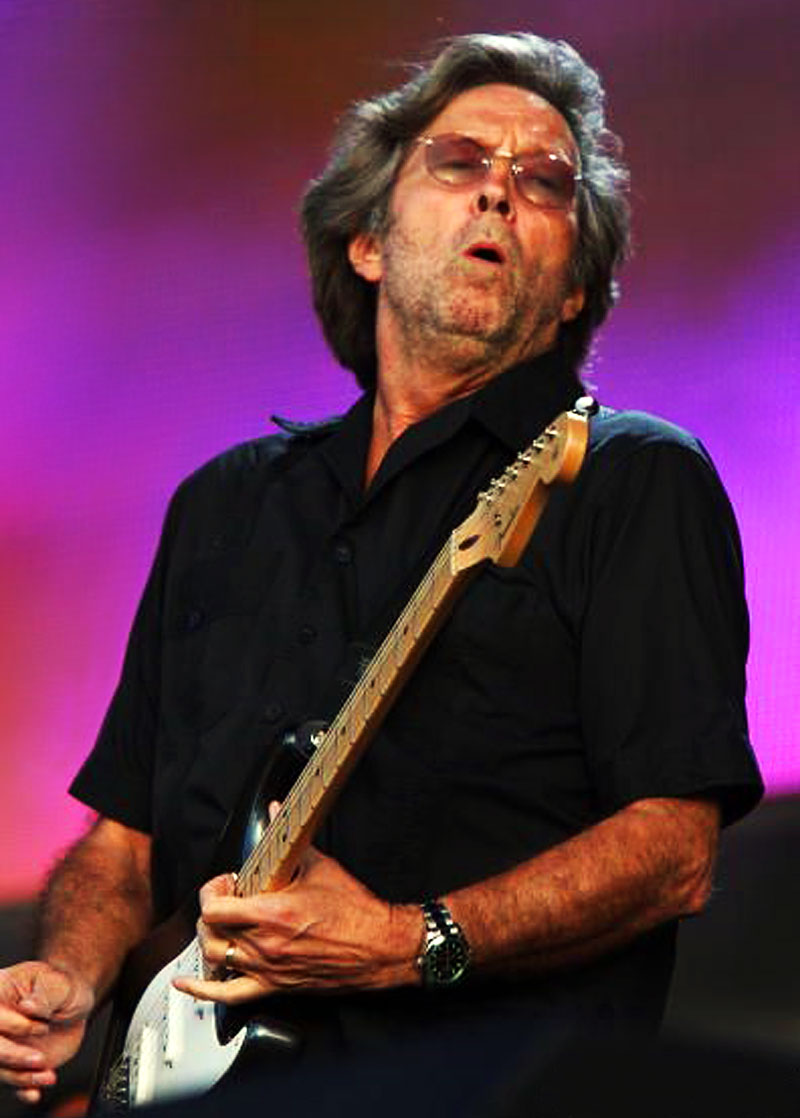

One night, unfortunately in a dream, Eric Clapton and I were onstage somewhere, jamming 12-bar blues, Chicago-style.

Of course, he was playing lead guitar. After a bit, he gave me the head nod universally understood by musicians to mean “your turn.†So off I ventured into an improvised solo, playing a few bars, then sent the spotlight back to where it belonged. Graciously, he again nodded, this time with his approval of my solo. That’s one way I knew it was a dream.

Switch to real life, on a Sunday night in St. Louis. I was out for a business dinner with colleagues, and being the hometown of Chuck Berry, we wanted to hear some music. We asked the cab driver to take us to any blues bar he could find, and ended up someplace we weren’t very welcomed, wearing ties and sports jackets.

But the bar did indeed have a great blues trio, Little Jimmy, whose band leader cautiously visited us during a break. He found out I was also a guitarist, invited me up to play lead on a few improvised bars of Who Do You Love? with his band, and the nasty looks from our fellow patrons turned to handshakes and pats on the back. It was the most localized and welcomed example of music’s healing power that I’d ever experienced.

Flash forward again, this time to Kitchener last week. There, the first of a province-wide series of discussions took place about the value of university research and innovation, its significant influence on society and how it will shape the future — specifically, the year 2030. Among the featured speakers was University of Guelph Prof. Ajay Heble, a fine jazz improvisation musician, who took the stage to talk not about scales, notes and other aspects of music, as you might expect. Instead, he spoke of hope.

To him, musical improvisation offers a foundation for hoping and dreaming of different and better days ahead. Sharing the spotlight speaks to a scenario where people get along through flexibility, trust and mutual respect. Those principles can lead to dialogue and a future where activists don’t need to shout to be heard, and to policy creation where artists are as involved as bureaucrats.

At the Kitchener gathering, which I wrote about in my Urban Cowboy column in the Guelph Mercury, Heble cited cultural studies scholar Ien Ang’s position on the future. She says one of the most urgent predicaments of our time can be described in deceptively simple terms: that is, how are we to live together in this new century? Indeed, before we figure out how we’ll exist in the next century, we’d better figure out how we’ll get through this one.

The early part of this century, the part we’re in right now, is pivotal for the future. Perhaps most notable is that we face the pending need to not only feed an estimated two billion more people in 40-ish years from now, but just as pressing, we must figure out how to do so. By 2030, the year chosen as a focus for last Wednesday’s discussion, it won’t be good enough to simply have plans in place. We’ll need to be actively working on them, too.

This doesn’t mean everyone involved in policy formation and food production must suddenly agree on everything. But more voices must be heard. The Idle No More movement shows what happens when people are ignored. They, too, are part of the future. They deserve the chance to shape it.

Heble’s approach has as much relevance in rural Canada as urban Canada, onstage or off, in municipal councils or boardrooms. Musicians take risks when they improvise, and for the most part the results are new and fresh. To Heble, that’s the way to the future.